The following meditation was written by Dr. Doug Hood’s son, Nathanael Hood, MA, New York University; MDiv, Princeton Theological Seminary

“These words that I am commanding you today must always be on your minds…tie them on your hand as a sign. They should be on your forehead as a symbol. Write them on your house’s doorframes and on your city’s gates.”

(Deuteronomy 6: 6,8,9 (Common English Bible)

Throughout the world, if you visit a religiously observant Jewish household, you’ll likely notice a tiny tilted cylinder called a mezuzah affixed to their doorposts. Usually no more than a few inches in size, a mezuzah—or the plural “mezuzot”—is commonly inscribed with nothing but the Hebrew letter “ש,” an abbreviation for the word Shaddai which both Jews and Christians will recognize as one of God’s many names in the Bible. With a handful of exceptions, mezuzot are placed in each doorway within a Jewish household. These mezuzot are not solid talismans but hollow containers holding a parchment scrape inscribed with verses from the Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament. There are many rules and regulations surrounding their construction, installation, and maintenance—only a specific kind of parchment can be used, the verses must be written by a specifically trained scribe, they must be affixed within a specific time frame after moving in, a specific blessing must be said as they’re installed, and they must be specifically checked for deterioration or damage every few years.

For religious outsiders, this might seem quite the hassle! After all, when observant Christians put up crosses or crucifixes in our homes, we don’t usually have a clergyperson make, install, and maintain them! But for observant Jews, mezuzot are not simple ornaments—they fulfill one of the 613 mitzvot or “commandments” required of them in the Torah, specifically the command from the Book of Deuteronomy to affix God’s words to their “doorframes and on [their] city’s gates.” What respect! What piety! What gratitude. And “gratitude” is the proper word here, for the bestowal of the Torah and its 613 mitzvot is considered by Jewish people as cause for joy and celebration. Mezuzot, therefore, are not grim, compulsory reminders of religious doctrine, but everyday reminders that they are God’s precious covenant people.

As early Christianity diverged from traditional Judaism in the first and second centuries AD and became a religion dominated by Gentile converts, we discarded most of the 613 mitzvot—including the use of mezuzot. But there are times when I wonder whether Christianity may have lost something precious by abandoning them. I think, in particular, of a dear friend in New York City who identifies as Modern Orthodox and has mezuzot posted all throughout his apartment. I’m always deeply moved by how he’ll reverently touch them as he passes them by, lifting his hand to his lips to kiss the fingers that themselves have touched God’s words.

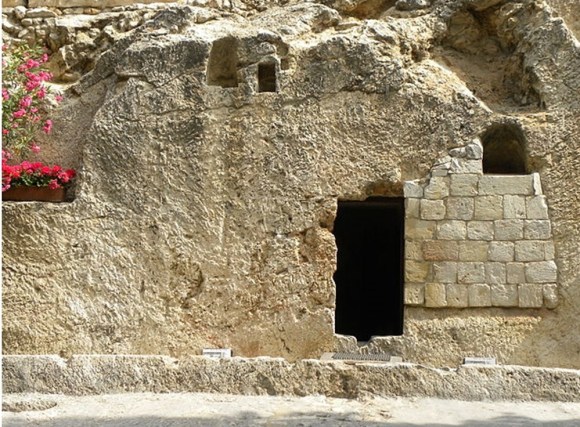

Understand this—I’m not advocating the Christian “reclamation” of mezuzot, but I do believe we stand to learn from our Jewish neighbors’ model of everyday religious gratitude. Too often, we Christians limit our devotions to one hour of worship on Sunday morning and to prayers before meals and bedtime. But if the promises of the Gospels are true—if we truly are redeemed from sin through Christ and guaranteed everlasting life—why shouldn’t we express a similar kind of gratitude? A joyous, sometimes euphoric everyday gratitude of amazement that, sinners though we be, we too have been chosen and redeemed, blessed and protected, cherished and beloved? So while we maybe shouldn’t affix Gospel verses to our doorposts, perhaps we Christians should strive in our own way to keep our gratitude alive and fresh all the days of our lives, in all our comings and goings. What other proper response could there be for a redemption such as that earned on the cross?

Joy,